Athletes across India are consuming more protein than ever before.

Protein shakes before training. Protein bars between sessions. High-protein diets proudly tracked on apps. Yet despite hitting — or even exceeding — recommended protein targets, many athletes report the same frustration: muscle gain is minimal, recovery is slow, and strength plateaus persist.

The assumption is simple: more protein equals more muscle.

Physiology tells a different story.

Muscle gain is not determined by protein intake alone. It is the outcome of a complex biological sequence involving digestion, absorption, amino acid utilization, inflammation control, gut health, nervous system recovery, and hormonal signaling. When any of these links break, protein becomes nutritional intent — not muscle tissue.

The Protein Paradox: Intake vs Utilization

Protein consumption is only the first step.

For dietary protein to become muscle, it must pass through several stages:

- Efficient digestion into amino acids

- Effective intestinal absorption

- Transport into circulation

- Cellular uptake by muscle tissue

- Activation of muscle protein synthesis (MPS)

- Recovery environment that allows adaptation

Failure at any stage limits results — regardless of intake.

This explains why athletes with similar protein consumption can experience vastly different outcomes.

Gut Health: The way to Muscle Gain

The gastrointestinal tract is not merely a digestion tube. It is a metabolically active organ system central to nutrient utilization.

Protein digestion begins in the stomach and continues in the small intestine, where enzymes break proteins into amino acids. These amino acids must then be absorbed through the intestinal lining.

When gut health is compromised:

- Enzyme production declines

- Intestinal permeability increases

- Absorption efficiency drops

- Inflammatory signalling rises

Common contributors in athletes include:

- Chronic stress

- Poor sleep

- Frequent NSAID use

- Inadequate fibre intake

- Repeated infections

- High training load without recovery

In such conditions, protein passes through the system incompletely utilized — appearing adequate on paper but insufficient at the cellular level.

The Gut Microbiome: The Hidden Regulator

The gut microbiome — trillions of microorganisms residing in the intestine — plays a critical role in protein metabolism.

Healthy microbial diversity supports:

- Amino acid synthesis

- Nitrogen balance

- Anti-inflammatory signaling

- Intestinal barrier integrity

Disrupted microbiota (dysbiosis) impairs these processes and increases systemic inflammation. Emerging research shows that poor microbial diversity reduces the efficiency with which dietary protein contributes to muscle protein synthesis.

In practical terms: an inflamed gut cannot build muscle efficiently, regardless of intake.

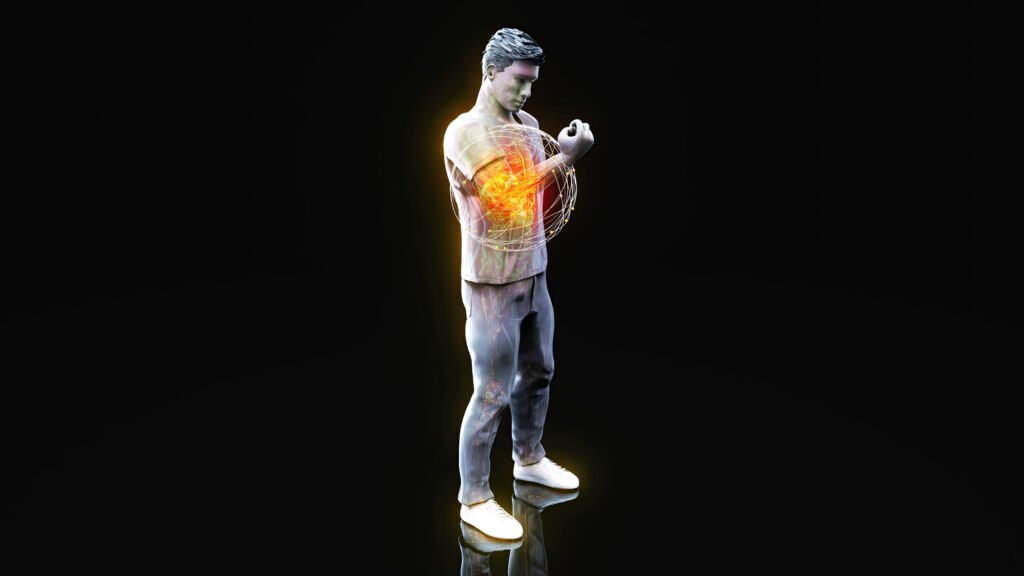

Inflammation: The Silent Muscle Killer

Muscle growth requires inflammation — briefly and locally.

Chronic inflammation, however, is destructive.

When systemic inflammation remains elevated:

- Muscle protein breakdown increases

- Anabolic signalling pathways (mTOR) are suppressed

- Amino acids are diverted toward immune function

- Recovery slows dramatically

Athletes often experience chronic inflammation due to:

- Under-recovery

- Poor sleep

- Excessive training load

- Nutrient deficiencies

- Gut dysfunction

In this state, protein is prioritized for survival — not hypertrophy.

Amino Acid Availability vs Amino Acid Utilization

Consuming protein does not guarantee amino acids reach muscle tissue.

Leucine — a key trigger for muscle protein synthesis — must cross multiple physiological checkpoints. Insulin sensitivity, blood flow, hormonal balance, and cellular signaling determine whether amino acids stimulate growth or remain unused.

Common barriers include:

- Insulin resistance

- Poor post-exercise nutrient timing

- Low carbohydrate availability

- Inadequate total energy intake

Low energy availability is particularly damaging. When the body senses insufficient energy, it suppresses anabolic processes to conserve resources. In this environment, protein intake supports maintenance — not growth.

Recovery: The Environment Where Protein Works

Muscle is not built during training. It is built during recovery.

Protein intake without adequate recovery is biologically inefficient. Muscle protein synthesis requires:

- Parasympathetic nervous system activation

- Adequate sleep duration and quality

- Hormonal normalization

- Low systemic stress

Athletes training intensely with poor recovery remain in a catabolic state — where muscle breakdown outpaces synthesis. Protein consumed under these conditions is oxidized for energy or diverted to repair, not growth.

The Nervous System–Muscle Connection

Muscle hypertrophy depends not only on nutrients but also on neural readiness.

Chronic nervous system overload reduces:

- Motor unit recruitment efficiency

- Training quality

- Hormonal anabolic response

When the nervous system is under-recovered, the training stimulus weakens. Even with sufficient protein, the signal required to trigger muscle adaptation remains inadequate.

This explains why athletes often eat well but fail to gain muscle during periods of psychological or neurological stress.

Micronutrients: The Forgotten Limiter

Protein metabolism depends on micronutrients.

Deficiencies in:

- Zinc

- Magnesium

- Iron

- B-complex vitamins

- Vitamin D

impair enzymatic reactions involved in protein synthesis, oxygen delivery, and recovery.

Micronutrient deficiencies are common among Indian athletes due to:

- Limited dietary diversity

- Vegetarian diets without strategic planning

- High sweat losses

- Inadequate supplementation oversight

Without correcting these deficits, protein utilization remains suboptimal.

Timing and Distribution: When Protein Matters

Protein distribution across the day influences muscle protein synthesis.

Large single doses do not compensate for long gaps. Frequent, evenly distributed protein intake supports sustained anabolic signalling.

Equally important is post-training timing, where protein must be paired with carbohydrates to enhance insulin response and amino acid uptake.

Protein alone does not maximize recovery. Context matters.

When More Protein Becomes Counterproductive

Excess protein without adequate digestion, fibre, hydration, and recovery can worsen gut dysfunction.

Symptoms include:

- Bloating

- Poor appetite

- Digestive discomfort

- Altered bowel habits

In these cases, increasing protein further compounds the problem. The solution is optimization, not escalation.

Rethinking Muscle Gain: A Systems Approach

Muscle gain is not a nutrition problem alone.

It is a systems outcome dependent on:

- Gut integrity

- Microbiome balance

- Inflammation control

- Nervous system recovery

- Energy availability

- Hormonal balance

- Training quality

Protein works only when these systems support it.

The Real Question Athletes Should Ask

Not “How much protein am I eating?”

But:

- Am I absorbing it?

- Am I utilizing it?

- Is my recovery sufficient to allow adaptation?

- Is inflammation suppressing growth?

- Is my gut healthy enough to support muscle gain?

Until these questions are addressed, protein remains potential — not progress.

Building Muscle That Lasts

Athletes who build sustainable muscle do not chase numbers on nutrition labels alone. They optimize digestion, recovery, stress management, and training quality simultaneously.

They recognize that muscle gain is not forced by intake — it is earned through systemic readiness.

If your protein intake isn’t translating into muscle gain, the issue is not effort. It is physiology.

And physiology demands precision.